Tom Stilp, JD, MBA/MM, LLM, MSC

Jeff Bezos may become the World’s first trillionaire. As people are staying at home and buying more on line as a consequence of the COVID-19 pandemic, Amazon is getting bigger.

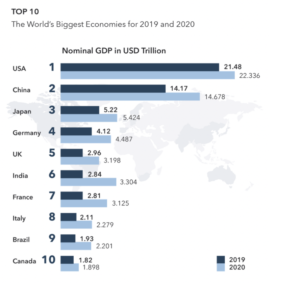

In prior In the Loop articles, we wrote that the U.S. has about 5% of the World’s population, but produces almost 20% of the World’s goods. Despite such large production numbers, the U.S. economy is extremely diverse, with manufacturing representing only 11% of the total economy.

The U.S. has retained its position of being the World’s largest economy since 1871, with $22.3 trillion in GDP. The U.S. has 24% share of the World GDP. (Source: www.Investopedia.com)

(Source: www.google.com/search?q=worlds+largest+economies)

To understand how things got so busy, we go back to the early American colonies and the corporation.

Historically, the English law, on which much of our law is based, allowed only the King and Parliament to grant a corporate charter. The use of the corporation was very limited, usually for a political purpose such as trade (consider the East Indian Trading Company in the movie, Pirates of the Caribbean). The King wanted to limit wealth and power by controlling economic opportunities and, therefore, subjects would be more beholden to the Sovereign.

In the early American Republic, corporations were disliked for different reasons. The Jeffersonians wanted to avoid large accumulations of wealth in private enterprises. Most companies, therefore, in the 1700s – 1800s were quasi-public entities, such as cities, boroughs, turnpikes, colleges and universities. State legislatures controlled, through special charters, the duration and types of activities that characterized corporations.

Competition among the States developed, including the opportunity for each State to get additional revenue in the form of franchise taxes paid by corporations. Permissive enabling laws were enacted and corporations grew.

The Mega-Rich, however, wanted to retain control. Andrew Carnegie operated his steel company as a limited partnership to avoid having to share control with his investors, and John D. Rockefeller used trusts to assemble oil companies under the banner of Standard Oil.

Eventually, Congress passed antitrust laws and broke up businesses when they got too big. (The foregoing is based in part on Klein, William A., Coffee, John C. and Partnoy, F., Business Organization and Finance (11th ed. 2010) pp. 112-117).

Today, forming a corporation usually requires nothing more than a few forms filed with the Secretary of State in which the business incorporates.

But unlike Carnegie Steel or Rockefeller’s Standard Oil, Amazon has millions of products, not just one. Thousands of other businesses feed into Amazon’s network.

Amazon handles not only distribution in its warehouses, but now has its own fleet of trucks, makes movies, and manufactures products. If Jeff Bezos were a country, he would be the 17th largest economy in the total of 189 World economies ranked by GDP. (Source: www.google.com/search?q=worlds+largest+economies)

In prior editions of In the Loop, we have written about checks and balances. Thomas Jefferson who favored a system of checks and balances would be awe-struck by the enormous companies of today.